An unclassified version of the long-delayed & long awaited 2022 Nuclear Posture Review has just been published. In a bureaucratic first, it's an attachment to the "2022 National Defense Strategy of The United States of America" released earlier today. No surprises. As expected, Biden has back-pedalled on his decades-long advocacy of "no-first-use" of nuclear weapons. In other words: Washington reserves its longstanding self-declared right to initiate nuclear strikes. This was almost inevitable because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Putin's murderous onslaught and reckless nuclear threats gave Biden no political room for his more progressive instincts. Nevertheless, POTUS has cancelled proposed new nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missiles, so expect howls of outrage from Republicans. However, such outrage will be exaggerated because: 1. From an operational perspective, the proposed new cruise missiles were always questionable. 2. The US is proceeding with the modernisation of its (a) Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles, or ICBMs, (b) ballistic missile-firing submarines, and (c) strategic bomber force. In fact, work is well advanced on new generations of these weapons. About US$600 billion is projected to be spent on these between now and 2030. 3. In addition to nuclear modernisation, overall US military spending remains vast -- about US$800 billion per year. While it's impossible to be precise with comparisons, even conservative estimates put this at about equivalent to the combined total for 2 x Russia plus China. Other estimates make the US advantage even wider. In addition, the next biggest spenders are nearly all US allies, none are enemies. 4. The US strategic edge is so significant that no American admiral or general would swap places with their Chinese or Russian equivalents. Update: here's a good discussion by Tom Nichols in The Atlantic. The 2022 NPT Review Conference wrapped-up on the weekend. Unsurprisingly, it was a failure. Some key states parties have for decades displayed a lack of seriousness about comprehensively meeting their obligations under the 1970 treaty, usually preferring a very selective approach, often based on narrow ideas of national interests. At this conference, an added factor was the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This war has poisoned the global arms control environment. A specific factor at the weekend was Moscow's vetoing of the conference's final document because it called for a stop to military operations in or near Ukraine's Zaporizhzya nuclear power plant.

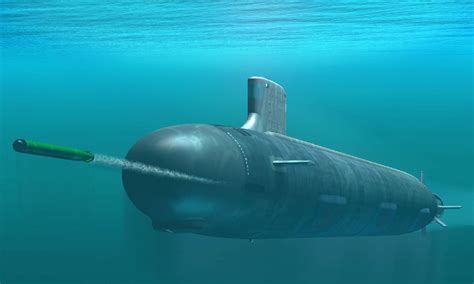

Interesting work from Peter Hartcher on the background to the Australian-UK-US submarine deal:

1. "Biden demanded bipartisan support before signing AUKUS. Labor was not told for months" 2. "Radioactive: Inside the top-secret AUKUS subs deal" 3. "AUKUS fallout: double-dealing and deception came at a diplomatic cost" A just released detailed overview of the US nuclear weapons arsenal, from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Includes an interesting essay on US nuclear developments since the Trump years. Here's a June up-date on the related congressional haggling, from the Arms Control Association.

Should NATO impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine? The future of Europe, and perhaps the world, hinges on the answer.

The call to arms has a strong moral pull. Innocent victims of aggression are pleading with the world’s most powerful alliance to stop the slaughter of civilians and the blotting out of a nation. Rather than drip-feeding supplies to Kyiv, which is said to betray a cynical willingness to fight to the last Ukrainian, is there not a humanitarian imperative for NATO to join the fight? There’s also a strategic case. Advocates claim that unless he’s stopped, President Putin will expand his aggressive agenda, probably into the Baltic states, and maybe beyond. They say refusal to secure Ukraine’s airspace reveals a dangerous weakness, inviting worse trouble down the track. Best that NATO steps in now, while the invading army is bogged down and much of the world is united in disgust at Russian war crimes. So far, these arguments have been trumped by fear of nuclear Armageddon, a prospect crassly manipulated by Putin to keep NATO at bay. Nevertheless, demands for Western armed intervention still surface with each new Russian atrocity. These demands are based on a belief that Putin is bluffing. Here we have decent people with humanitarian instincts gambling that they comprehend Putin’s mindset. But they probably can’t. There’s no sign that he has a conscience and considerable evidence he’s prone to upping the ante. On the other hand, today, Putin probably does understand that Russian escalation is unlikely to end well. So, let’s assume, for the moment, that Putin is bluffing and not inclined to go nuclear. Would that make a no-fly zone a reasonable option? Probably not, because, even then, the benefits of a no-fly zone might easily be outweighed by the risks. These risks include splitting the West. NATO’s primary mission is defence of member states. The narrow job description underpins the consensus holding the alliance together. It also prevents a slide into foolish military adventures. Since 1945, Europeans (unlike Americans) have mostly avoided confusing self-defence with power projection. Breaking the consensus will open cracks in NATO, presenting Putin with a win. But NATO isn’t holding back only for political reasons. Western supplied anti-aircraft missiles already make Ukraine’s airspace hazardous for Moscow’s warplanes, lessening the need for US and Russian pilots to go head to head. Also, the alliance wouldn’t expect the easy ride it had with previous no-fly zones over, say, Iraq and Libya. Ukraine’s air space will be more contested, requiring intense air combat and attacks on Russian ground-based anti-aircraft facilities. Destroying these will almost certainly produce unintended casualties. Furthermore, clearing the sky over Ukraine won’t stop the butchery. If the aim is to prevent towns being ground into rubble, pressure will build to go after the main sources of the devastation, which means bombing Russian artillery and going after missiles fired from Russia. Once a moral imperative for military action is accepted, there will be no clear boundary to the mission creep. When layered over crushing sanctions, an extensive NATO air operation could look to Moscow indistinguishable from an attempt to break Russia. No one knows what will then happen. NATO’s assertiveness might induce the Kremlin’s surrender, possibly through a palace coup. But it’s more likely to spark a retaliation. Don’t bet on Moscow leaving NATO bases untouched while they’re being used to destroy the Russian air force. At each step of an expanding war, the potential for more escalation will be baked-in. The scope for accidents will grow, the stakes will increase, and the resulting strategic adjustments could be hasty and prone to miscalculation. This type of escalatory dynamic will crossover into nuclear contingency planning. Both the Pentagon and the Russian General Staff believe conventional battles could generate pressure for nuclear strikes. It’s why neither Moscow nor Washington rule-out nuclear first-use. Furthermore, each believes deterrence requires convincing the other that it’s prepared to climb up the escalation ladder all the way to World War Three. The problem is that efforts to signal this resolve could backfire. If Russia does use a tactical nuclear weapon to shock NATO into halting an air offensive, expect the Alliance’s war plans to radically ramp-up. Then, rising alert levels for Russian and American strategic nuclear missiles could become mutually reinforcing, inadvertently propelling us towards a far nastier conflict. Whatever is going through Putin’s mind today will almost certainly be altered by the unfolding of such a train of events. Even if, today, he’s bluffing and privately set against escalation, the situation could take on a life of its own as the stresses of responding to an actual no-fly zone crowd-out pre-escalation assessment. Crisis management will then move to a different pace. The onus is on those calling for a no-fly zone to explain how it’s not equivalent to lighting matches in a room full of fireworks. Yet they have no convincing answer to how an expanded war ends well. Instead, advocates have combined outrage and ill-placed optimism, and then confused the mixture with a strategy. Heart-breaking pleas for a no-fly zone should be balanced against military advice, intelligence assessments and political judgment. President Biden and NATO know this. They also realise there’s no easy way to deal with a vicious, untrustworthy leader of a nuclear-armed great power subjugating a neighbour. Good policy here is relative, a choice between unsatisfactory and bad options. That points to keeping Moscow under pressure without triggering a bigger war, one that could wreck civilisation. . A new report from the US Congressional Research Service: "Russia’s Nuclear Weapons: Doctrine, Forces, and Modernization."

Ted Carpenter, veteran US defence analyst, explains some of the background to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Like Moscow, he puts much of the blame on NATO expansion. It's not an argument I'd endorse without some qualification, but it is an important part of the context.

One blindingly obvious consequence of Putin’s war is the damage done to global arms control (try convincing Washington/NATO to reduce their defence efforts after what we've just witnessed). There’s also a more technical aspect, albeit with a very politicised element. It concerns steps in the 1990s to convince Ukraine to surrender the nuclear weapons option. This article nicely summarises key points.

Hot off the press: here's an up-date on Russian nuclear forces, from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Here's a link to the latest reputable assessment of Israeli nuclear weapon capabilities. From Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

|

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed